The Task: Watch and write about every movie on my shelf, in order (Blu-rays are sorted after DVDs), by June 10, 2015. Remaining movies: 166+6 new=172 Days to go: 166

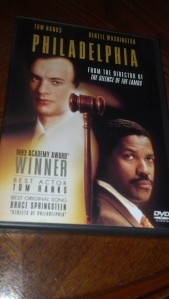

Movie #211: Philadelphia

In my experience, Tom Hanks has had two roles in which his entire persona has fallen away and only the character has remained. The second was Forrest Gump, notable in part because it placed him in contention with an elite group of actors who have had multiple Best Actor Oscar wins, let alone back to back. The first was Philadelphia.

In Philadelphia Hanks plays Andrew Beckett, an attorney at a prestigious firm in the city. He’s a legal rock star, slam dunking cases left and right, and being given one of the most high-profile clients to the firm in some time. He’s on the fast track to a partnership, but he’s living with AIDS — a fact that no one at the office is told. Andy’s illness progresses (exacerbated, no doubt, by the stress of his job) and he works on his case at home or off-hours to stay out of the office during his treatment and period of notable lesions. Unfortunately, something happens with the brief he’s prepared and no one is able to find it either on his desk or in his computer, uncovering it in central filing only at the last possible moment. Andy is blamed for this mishap and he is fired, for which he plans to bring suit against his employers (including Jason Robards as Charles Wheeler). He contends that he was fired for having AIDS, for keeping it from the partners, and for being a homosexual. And he has a case.

However, finding an attorney to represent him is another story. He goes to nine before he finds himself in the office of Joe Miller (Denzel Washington), a slick personal injury lawyer complete with obnoxious television spots and an ambulance chaser mentality. Joe doesn’t want this case either, though, and it’s obvious as to why. When Andy reveals his condition, Joe is immediately standoffish and paranoid. He doesn’t want to be anywhere near Andy, for fear of contracting the disease himself.

Joe is incredibly bigoted and prejudiced against homosexuals — enough so that it was uncomfortable to witness his vitriol even at a time when a lot of people publicly held similar views — but in the structure of the film he acts as an audience surrogate. In 1993 especially, Joe’s views of the gay community and of AIDS in general were common views, and Joe’s gradual enlightenment and acceptance of Andrew’s life and humanity mirror the kind of transformation that’s occurred in American society over the past twenty years. Vice President Joe Biden was mildly derided (as Joe Biden often is) when he made the claim that Will & Grace opened a lot of eyes to the idea of homosexuals being just like everyone else, but he wasn’t wrong. It’s the very idea that fuels the #WeNeedDiverseBooks movement as well — seeing a variety of people, of lifestyles, of cultures in the art and culture we consume helps us to understand and build tolerance and promote equality across the board. Will & Grace absolutely changed the public’s idea of what it means to be a homosexual, and it didn’t come out until 1998. When Philadelphia came out at the end of 1993, society was five years younger, five years less evolved, and Washington’s portrayal of a deeply close-minded and homophobic individual was vital because it was not at all unique or exaggerated. It was an authentic and honest portrayal. I don’t think he gets enough credit for that.

One of the ways Philadelphia seeks to humanize Andrew and make him more relatable to society at large is to equate his situation with that of the Civil Rights Movement. There are three scenes in which this is specifically accomplished, and yet as unmistakable as the moves are they are subtle enough to feel organic and earned in the world of the story. First there’s the library scene, in which Joe is the recipient of some suspicious glances, as if he doesn’t belong in a law library, just before Andrew himself is encouraged to go to a “private research room” — separate but equal — in order to not make the other patrons uncomfortable. This is the scene in which Joe himself realizes the similarities between the plights of these two groups of people. He starts to recognize the quest for acceptance as a universal one, and he decides to take Andrew’s case. Next there’s the scene in which Andrew is preparing his family for the trial, and despite his sister Jill (Ann Dowd in weird brassy blonde hair) fearing for what it will put their parents through, his mother (Joanne Woodward) says, “I didn’t raise my children to sit at the back of the bus.” She’s overtly and vocally making the connection that this is just another quest for civil rights, this time for the homosexual community instead of the black one. And then there’s the testimony of Anthea (Anna Deavere Smith) at trial, in which she describes her personal experiences with inconspicuous racism and discrimination (the kind that is not overt or hostile but is still mired in disdain and fear of the “other”) and chastises the defense counsel (Mary Steenburgen) for oversimplifying such a complex issue. This is to let us know that these prejudices exist in the shadows and corners of our lives, that we’re often not aware of them, but that they still have a negative impact overall. It’s that kind of statement that forces us to be more conscious of our own biases and to curb or correct them when we notice them arise. That’s a huge step of forward progress in our collective thinking for a movie to attempt, yet Philadelphia succeeds at it beautifully.

Another way Philadelphia opens the minds of Joe (and its viewers) is through Andrew’s family. Not only does he have a loving and committed relationship with his long-standing partner Miguel (Antonio Banderas), he has a large, accepting and wonderful family. He’s both a younger brother and an older one. He’s a cherished son. He’s a beloved uncle. If Andrew had had just one or two family members, their blind and unconditional acceptance of him might easily be written off as the obligation of people who don’t have anyone else. But that’s not the case here. Andrew has several siblings, all of whom have spouses and children, plus two supportive parents. They’re all behind him one hundred percent. They don’t hesitate to touch him. They hug and they kiss him. They treat him as any family would treat a beloved member who was dying, and by showing that as normal, as to be expected, the movie is once again showing Joe (and the audience) how like everyone else Andrew really is. It seems crazy to me that this is a thing that needed (that still needs, actually) to be expressed, but it did, and it worked. The public perception and acceptance of the LGBT community has undergone overwhelming transformations in the twenty-one years since Philadelphia came out, and while this one movie didn’t make all the difference, it definitely made some. At the end of the film, when Joe is securing Andy’s oxygen mask and touching his face, it’s a lovely expression of intimacy and trust and friendship that has completely superseded all his previous fears, scorn and reservations.

It’s such a powerful moment, in fact, it would be an understandable and effective end point for the film, but Philadelphia thinks Andy (and the millions of other lives lost to AIDS) deserve better. The film is not going to end focusing on Andy’s death, but on his life. So when Joe gets the call from Miguel in the middle of the night, and family and friends start to gather at Miguel’s following funeral services we don’t get to see, the camera pans around to all the lives Andy’s touched, to all the lives of his nieces and nephews and brothers and sisters that are continuing on, and on the home videos of his youth — so much like every other youth of his generation — with his curls, his cowboy costumes, his baseball playing, and his running on the beach. His was a life like any other, filled with love and treasured memories. It’s a beautiful and necessary sentiment, and I love that the movie ends on that note.

Philadelphia is not the sort of film that I associate with rich visuals or luxe cinematography (although there are some lovely and affecting shots used here and there), but it’s the kind of film that sneaks up on you, I think. It takes up residence in your mind and becomes part of your thought process, your perceptions, your perspectives. And that’s how it’s most effective. That’s where it really makes an impact that stands the test of time.

That’s what makes Philadelphia such a great and important film.